The 2021 BBWAA

Hall of Fame ballot will mark the first time in nearly a decade that no

first-time eligible candidates are expected to draw close to the

necessary 75% of the vote required for election. Nevertheless, the

upcoming ballot features a few newly-eligible candidates with intriguing

Hall of Fame cases who could build towards eventual election.

Arguably, the first-time candidate with

the strongest Hall of Fame case is right-handed pitcher Tim Hudson. During a solid career which spanned from 1999 to 2015, Hudson pitched

for three teams: the Oakland Athletics, Atlanta Braves, and San

Francisco Giants. Hudson was noted for his mastery of the sinkerball

which he used to frustrate opposing hitters by generating weak contact

and inducing ground balls. Hudson

retired with a career win-loss record of 222-133 and a 3.49 ERA. When

Hudson’s career ERA is ballpark and league adjusted, his 3.49 mark

translates into a more illustrious 120 ERA+. In addition, Hudson

accumulated 57.9 career WAR during his career. Yet, Hudson’s most

impressive career statistic is his excellent .625 win-loss percentage,

which is the equivalent of a team posting a 101-61 record over the

course of a full season. Historically, a pitcher with the combination of

Hudson’s 222 victories and .625 win-loss percentage has been voted into

the Hall of Fame by the BBWAA or through one of the incarnations of the

Era Committee. However, wins have become devalued by some in the

baseball community and as a result Hudson may not receive the support he

would have from previous generations of voters. With

this in mind, I decided to take a deeper look into the validity of

Hudson’s win-loss percentage by comparing the righty to seven prominent

pitchers in a variety of categories that affect wins and losses. Rather

than just rely on the popular

traditional and sabermetric methods, I chose to take a different

approach by using some alternative advanced metrics and statistics to

analyze the pitchers.

The seven hurlers I am comparing Hudson to include:

•the three starting pitchers most recently voted into the Hall of Fame: Roy Halladay, Mike Mussina, and Jack Morris;

•the highest returning holdover candidate on the BBWAA ballot: Curt Schilling;

•two of Hudson’s contemporaries whom are also candidates on the upcoming ballot: Andy Pettitte and Mark Buehrle;

•as well as another contemporary who is not yet eligible but has a strong chance at being elected to Cooperstown: CC Sabathia.

The Rare Combination of Hudson’s 222 Wins and .625 Win-Loss Percentage

Before

delving into the comparisons, I wanted to see how rare it is for a

pitcher to retire with Hudson’s impressive combination of career

victories and win-loss percentage. In fact,

only 16 pitchers have completed their careers with more victories than

Hudson’s 222 while also posting a higher win-loss percentage than the

righty’s .625 mark. To date, 14 of those 16 pitchers are in the Hall of Fame while the two hurlers who have yet to be elected,

Roger Clemens and Andy Pettitte, are still on the BBWAA ballot. Of

course, Clemens’ and Pettitte’s Hall of Fame candidacies have each been

adversely affected by their ties to PEDs. Had it not been for the PED allegations, Clemens would have been an

easy first ballot or even unanimous Hall of Fame selection while

Pettitte would have certainly drawn a much higher vote total than the

respective 9.9% and 11.3% he collected in his first two years on the

ballot.

However, Hudson’s 222 victories and .625 win-loss percentage represent the minimum of the standard. Nevertheless,

if the standard is changed to pitchers with 200 victories and a .600

win-loss percentage, Hudson still belongs to a very exclusive club as he

is one of just 37 hurlers to retire with this impressive statistical

combination. Moreover, 28 of those 37 pitchers are in the Hall of Fame. Aside from Hudson, the remaining hurlers sitting outside of Cooperstown who

retired with the 200 victory/.600 win-loss percentage combination

includes the aforementioned Clemens and Pettitte and also adds the

yet-to-be eligible Sabathia along with David Wells, early 20th century

right-hander Carl Mays, and a trio of 19th century pitchers—Charlie

Buffinton, Bob Caruthers, and Jack Stivetts. Other than Sabathia, Hudson’s career is a healthy step above these additional hurlers as

Mays and Stivetts only just clear the 200-victory threshold while

Wells, Buffinton, and Stivetts barely meet the .600 win-loss percentage

standard. Mays has appeared on the Veterans Committee ballot in the past but has never come close to election. His Hall of Fame case has been overshadowed

by throwing the errant pitch that killed Ray Chapman and suspicion that he

purposely lost World Series games during the 1921 and 1922 Fall

Classics. The

trio of 19th century hurlers have never been serious Hall of Fame

candidates as each had careers that were barely a decade long, played

during an era when two or three-man pitching rotations were the norm

and the disparity between the best and worst teams was more pronounced. Wells

is the only pitcher of recent times to retire with the 200 victory/.600

win-loss percentage combination and fall off the BBWAA ballot. However, Wells’ Hall of Fame case was likely doomed by his 4.13 career ERA which would be, by far, the highest in Cooperstown.

Career Totals as a Starting Pitcher

Since

the majority of the stats I am using reflect the hurlers’ performances

in games in which they were the starting pitcher, their career record,

win-loss percentage, and ERA shown below slightly differ from their overall career totals.

The

pitchers I consider most fitting to compare Hudson with are Buehrle,

Halladay, Pettitte, and Sabathia because their career timelines most

overlap with Hudson’s. Keep in mind, Hudson is being judged against

hurlers who have promising Hall of Fame cases or are already enshrined

in Cooperstown. It is certainly possible that each of these pitchers

will one day find their way into the Hall of Fame either through the

BBWAA vote or on a later Era Committee ballot. Thus, being at or near

the mean of these pitchers in these categories is impressive.

Percentage of Games Started Won and Lost

During his career, Hudson regularly won while rarely losing. In fact, Hudson finished with a sub-.500

win-loss percentage in just two of his 17 major league seasons. Moreover, Hudson had just four double-digit loss campaigns, including

two where he lost exactly ten games. By contrast, Hudson had 13 seasons with double-digits in wins. Hudson’s career-high total of defeats was just 13—a total he met or exceeded in victories ten times during his career.

The

tables above show Hudson is slightly below the mean among the eight

hurlers in percentage of games started where he was credited as the

winning pitcher. However, Hudson really shines in the low percentage of

games started where he was tagged as the losing pitcher. Hudson took

the loss in just 27.77%

of his starts, trailing only Halladay who easily leads the octet of

hurlers in both categories—underscoring why “Doc” is the only

first-ballot Hall of Famer of the group. These

two categories also illustrate how Hudson won with more regularity than

contemporaries Buehrle and Sabathia and lost with less frequency than

Pettitte, Buehrle, and Sabathia.

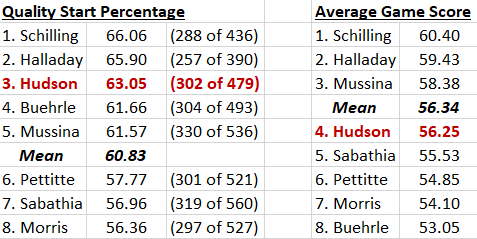

Quality Start Percentage and Average Game Score (Version 2.0)

Quality start and game score are two useful metrics to evaluate a starting pitcher’s performance.

A pitcher is given credit for a quality start when they pitch six or more innings while giving up three or fewer earned runs. When

a starting pitcher is removed from the game, you’ll often hear a

commentator remark, “he gave his team a chance to win” or “he kept his

team in the game.” If a hurler has a quality start, they’ve essential pitched well enough

to earn the win or have, at the very least, kept the game close by

limiting the opposing team’s scoring.

Game

score is a metric which gauges a starting pitcher’s performance by

converting it into a number figure based on the quantity and quality of

the outing. Game score was originally devised by Bill James, however, I

prefer Tom Tango’s refined version of the metric because it uses a

slightly different formula which penalizes pitchers for giving up home

runs, something James’ version does not do.

At

63.05%, Hudson is comfortably above the mean in percentage of quality

starts and a good distance ahead of Pettitte, Sabathia, and Morris. For

average game score, Hudson’s 56.25% is an eyelash below the 56.34%

mean. The three pitchers Hudson trails in average game score are a pair

of Hall of Fame hurlers, Halladay and Mussina, along with Schilling—who

if it hadn't been for a crowded ballot and his off-the-field

controversies, would have been voted into Cooperstown several years ago.

Cheap Wins and Tough Losses

A cheap win is when a starting pitcher earns the victory in a non-quality start by pitching fewer than 6 innings or allowing more than 3 earned runs.

With

just 28 of his 222 career triumphs being classified as cheap wins,

Hudson rarely was the recipient of a gifted victory despite making a

non-quality start. Hudson’s 12.61% mark ranks a strong third among the eight hurlers and is easily better the 15.70% mean.

Essentially

the opposite of a cheap win, the pitcher is credited with a tough loss

when they are the losing pitcher of record in a quality start.

This

is the first category in which Hudson looks poor in comparison to the

featured hurlers. With 35 of his 133 career defeats coming in quality

starts, Hudson is about 5 tough losses below the mean. Nevertheless,

Hudson’s solid average game score mark somewhat nullifies his lower

number of tough losses. Interestingly,

Hudson’s highest percentage of tough losses came in 2014 when the

righty posted a career-worst 9-13 record for the San Francisco Giants

despite making quality starts in seven of those defeats. Hudson’s

losing record was largely the byproduct of being a victim of

particularly poor run support as San Francisco’s offense scored zero or

one run in each of the seven games in which the sinkerball-specialist

made a quality start but was tagged with the loss. Yet, it all worked

out for Hudson and the Giants as the season ended with the veteran

lifting the World Championship trophy over his head after the club beat

the Kansas City Royals to win the 2014 Fall Classic.

Wins Lost and Losses Saved

The

wins lost table shows how often the eight pitchers were in the position

to be credited for the victory at the time they faced their final

batter, only to be denied the win due to their bullpen blowing the lead.

Hudson has the dubious honor of leading the octet of hurlers in wins lost. Over the course of his career, Hudson lost a staggering 50 potential wins due to his bullpen blowing leads. In fact, the lead

Hudson holds over the other pitchers is so significant that the difference

between the sinkerballer’s 10.44% wins lost mark and the 8.46% of the

second-highest placing hurler, Roy Halladay, is greater than the gap

from Halladay to the 6.61% total of the next-to-last ranked CC Sabathia.

Hudson

spent the early part of his career with the Oakland Athletics. Along

with Mark Mulder and Barry Zito, Hudson was part of an impressive trio

of young starters known as the Big Three. Before being split up by

Hudson’s and Mulder’s respective trades to the Atlanta Braves and St.

Louis Cardinals following the 2004 season, the Big Three helped lead the

A’s to three AL West Division Titles and one AL Wildcard. Unfortunately for Hudson, Oakland’s bullpen had a bad habit of costing

him wins. Hudson was particularly victimized between 2002 and 2004 when

the A’s relief corps cost the sinkerballer 18 potential wins. Taking

a deeper look into the game logs, only one of those 18 probable

victories were lost as a result of Hudson leaving a runner on base. What’s

more, Hudson’s leads were often blown by the A’s closers during those

years as Billy Koch squandered 3 of the 8 potential victories the

bullpen cost Hudson in 2002 while Keith Foulke accounted for all 4 of

Hudson’s probable wins that were lost in 2003. However, because

Oakland’s potent offense was able to retake the lead when they were the

pitcher of record, Koch was credited with the win for all three of the potential victories he cost Hudson while Foulke

picked up the “W” for two of the four probable victories he cost

Hudson. Despite blowing Hudson’s potential wins, Koch and Foulke were

each named the respective AL Rolaid Relievers of the Year in 2002 and

2003. While Oakland’s bullpen struggled to hold Hudson’s leads, it was

certainly not due to the righty coming out of games too quickly as he

regularly pitched deep into ballgames, averaging 7 innings per start

between 2002 and 2004. Moreover, Hudson ranked third among AL hurlers for innings pitched in both 2002 and 2003.

The

antithesis of wins lost, losses saved accounts for the number of times

the eight hurlers were in position for the loss but their team came back

to tie the game or take the lead, thus saving them from being the

losing pitcher of record.

Hudson

ranks fifth with an 8.56% losses saved mark that is a tick better than

the mean. Hudson is a good distance in front of sixth place Schilling

and is well ahead of his contemporaries, Buehrle and Sabathia, who bring

up the rear. Among

the eight pitchers, Hudson along with Hall of Famers Halladay and

Mussina are the only ones with more wins lost than losses saved.

“Adjusted” Win-Loss Percentage

Cheap

wins and tough losses essentially have their respective opposites in

wins lost and losses saved. As the previous tables illustrate, some

hurlers excel amongst their fellow pitchers in one category while

struggling by comparison in another. However, by deducting cheap wins

and tough losses from the pitcher’s career totals while adding wins lost

and losses saved to their ledger, an “adjusted” career win-loss

percentage is created which gives an idea of the eight hurlers’ overall

performance in those four categories. The table below shows each

pitcher’s “adjusted” starting pitcher career win-loss record and the

increase or decrease from their “adjusted” to their actual starting

pitcher win-loss percentage.

Hudson

once again finds himself among Hall of Famers as his .0117 increase

from his actual to “adjusted” win-loss percentage ranks second, in

between Halladay and Mussina. Hudson and Halladay are the only two

hurlers who have more tough losses than cheap wins as well as a greater

number of wins lost than losses saved. Hudson’s

contemporaries, Pettitte and Sabathia, stand out in a different way as

they are the only two pitchers to see a decrease from their actual to

“adjusted” win-loss percentage. In fact,

Pettitte’s and Sabathia’s decreases are so significant that they bring

the mean all the way down to .0040 with each of the other six hurlers

comfortably above it.

Run Support

Aside

from National League pitchers occasionally helping their own cause, the

level of run support a hurler receives from their offense is out of

their control. Nevertheless,

run support can have a major effect on a pitcher’s win-loss record. Run support is judged in two different ways: run support per game which

measures runs scored for the entire game per 27 outs and run support

per innings which accounts for runs scored per 27 outs while the

starting pitcher was in the game. Below are each of the hurler’s career

run support per game and per innings versus the MLB average which is in

parentheses. These tables are followed by the combined differences between each pitcher’s run support per game and per inning versus the MLB average during their career.

Hudson

ranks second behind Schilling on all three tables. However,

calculating a true ranking based on run support is difficult since a

pitcher’s run support is affected by a variety of factors that are

unique to each hurler including the pitcher’s home ballpark, the

division their team played in, and the era during which their career

took place. For example, the hurler with, by far, the lowest run

support is Schilling who spent eight-and-a-half years of his career

playing for the offensively-challenged Philadelphia Phillies who

finished at or near the bottom of the NL in runs scored during the bulk

of his time with the club. Conversely, the pitchers with highest run

support are Pettitte and Mussina who respectively spent the majority and

entirety of their career’s playing in the high-offense AL East during

what is often referred to as the Steroid Era. Nevertheless,

aside from Schilling, it does not appear Hudson benefited from higher

run support in comparison to the featured hurlers.

Individual Starting Pitcher Win-Loss Percentage vs. Team Win-Loss Percentage

During

his career, Hudson generally pitched for competitive teams. In fact,

just two seasons of Hudson’s 17-year career were spent with a team that

finished the campaign with a sub-.500 record. Thus, a Hall of Fame

voter might

assume the hurler’s excellent .625 win-loss percentage is a byproduct of

playing the majority of his career with competitive teams. Nevertheless,

it is also true that the best pitchers will generally play the bulk of

their careers with winning teams, in part, because their services will

be sought by the most competitive franchises. Indeed, the Braves made a

deal with the A’s to acquire Hudson as the right-hander was approaching

free agency and quickly signed him to a lucrative contract extension to

keep him from testing the open market. And, towards the end of Hudson’s career, the Giants signed the hurler

to add veteran depth to their rotation as the club embarked on its third

Championship run in five seasons. While Hudson’s services were in

demand by contending teams, it is undoubtedly true his win-loss record

was enhanced by playing for competitive franchises. However, most of

the featured hurlers followed the same pattern of spending a significant

portion of their careers with winning ballclubs. The table below illustrates which pitchers benefited most from playing for competitive franchises by showing

the difference between each’s individual win-loss percentage as a

starting pitcher versus the accumulated win-loss percentage for the

teams they played for during their career.

The teams Hudson played for during his career put together an overall win-loss percentage of .553 which is roughly the equivalent

of a club posting a 90-72 regular season record while the righty’s .625

individual career win-loss percentage translates to a 101-61 record

over the course of a full season. The .072 difference between Hudson’s

individual win-loss percentage versus the .553 mark of the teams he

played for ranks the sinkerball-specialist fourth among the eight

hurlers, just shy of the .077 mean. Hudson’s win-loss percentage was

aided by playing for competitive franchises but it is also evident that

he outperformed his teams in comparison to his contemporaries Sabathia, Buehrle, and Pettitte as his .072 mark is comfortably ahead of each of these hurlers.

Average Finish in the Ranked Categories

To

give an overall picture of how Hudson stacks up among the eight

pitchers here is the average finish of the featured hurlers based on

their classification in the ranked categories. I chose

to omit the three run support tables from the rankings because there

are too many variables and not a clear enough picture to give an

accurate ranking. I

also excluded “adjusted” win-loss percentage from the rankings since it

is a composite of cheap wins, tough losses, wins lost, and losses

saved.

Hudson’s

3.89 average finish ranks the sinkerballer fourth among the eight

pitchers. Hudson’s combined rankings from the nine categories add up

to 35 points, putting him just three points behind overly-qualified Hall

of Fame candidate Schilling and two points away from 2019 Cooperstown

inductee Mussina. Hudson is above the mean in five of the nine ranked

categories. What’s more, the

righty sits well above the mean in four of those categories: lowest

percentage of games started lost, average quality start percentage,

lowest percentage of cheap wins, and highest percentage of wins lost. By contrast, Hudson is well below the mean in only one metric: highest

percentage of tough losses.

As

for the seven other featured hurlers, not surprisingly Halladay leads

his fellow pitchers by a sizable gap. In fact, Halladay ranks first or

second in seven of the nine categories and his 17 points from the

combined rankings translates to an average finish of 1.89. With such a

wide margin separating Halladay from the three-way battle for second

place between Schilling, Mussina, and Hudson, it is clear that among the

nine ranked categories the first-ballot

Hall of Famer is truly in a class by himself. A ways back from the

Schilling-Mussina-Hudson triumvirate, Buehrle and Pettitte are tied for

fifth place with their equivalent 48

points giving them each a 5.33 average finish. Further back is Morris

with 55 points and a 6.11 average finish while Sabathia is dead last with 56 points and a 6.22 average.

Morris’

seventh place rank is not surprising since his 3.90 ERA is the highest

among Hall of Fame pitchers. Nevertheless, Morris’ Hall of Fame case

was greatly strengthened by his stellar World Series performances during

the 1984 and 1991 Fall Classics, each of which played a role in his

election to Cooperstown. However, Sabathia’s last place finish is somewhat unexpected. During the final season of his career, Sabathia

joined the prestigious 3,000-strikeout club while also reaching the

secondary milestone of 250 wins. Reaching these dual milestones will

undoubtedly help Sabathia draw support when he becomes eligible to

appear on the BBWAA ballot in four years. That being said, Sabathia’s

low ranking is due, in part, to his pitching several seasons past his

prime. With 3577.1 innings pitched, Sabathia ranks second among the

eight hurlers, behind only Morris’ 3824 frames. This longevity enabled

Sabathia to reach the 250-win/3000-strikeout milestones but the quantity

he added also came at the expense of quality as, over the final seven

seasons of his career, the hurler often struggled to pitch at a league

average level, going 60-59 with a 4.33 ERA while posting a pedestrian

ERA+ of 97. Moreover, during Sabathia’s final seven campaigns, the

veteran was the beneficiary of 16 cheap wins and saved from a staggering

31 potential losses compared to being the victim of 14 tough losses

with just 5 potential wins lost.

While Hudson’s 3.89 average finish and fourth place ranking puts him in the neighborhood of Schilling and Mussina, many

of the popular sabermetric stats such as WAR and JAWS judge the

sinkerball-specialist’s career value as being closer to his

contemporaries, Buehrle, Pettitte, and Sabathia. Nevertheless,

with Hudson’s strong overall showing in the nine categories, the righty

sets himself apart from Buehrle and Pettitte, whom he is slated to

share the upcoming ballot with. Hudson also distinguishes himself from

Sabathia, who will be eligible for the 2025 vote. In addition,

Hudson’s solid ranking and the edge he holds over three of his

contemporaries underscores the validity of his 222 victories and .625

win-loss percentage. Wins may be devalued by some in the baseball

community, however, the rarely seen combination of Hudson’s victory

total and win-loss percentage are key elements of a Hall of

Fame-caliber career that should one day earn the hurler a bronze plaque

in Cooperstown.

----by John Tuberty

Cards: Tim Hudson 2002 SP Authentic,

Mark Buehrle 2002 Upper Deck Ballpark Idols, CC Sabathia 2010 Topps, Roy

Halladay 2006 Fleer Ultra, Mike Mussina 1996 Topps, Andy Pettitte 1996

Fleer, Curt Schilling 2000 Upper Deck Pros & Prospects, Jack Morris

1984 Fleer, Tim Hudson 2007 Upper Deck, Tim Hudson 2014 Bowman Chrome,

Tim Hudson 2002 Topps Reserve, Tim Hudson 2006 Upper Deck Sweet Spot

Update, Curt Schilling 2004 Fleer Ultra, Mike Mussina 2003 Upper Deck

First Pitch

Other Articles by Tubbs Baseball Blog:

Stat links to players

mentioned: Tim Hudson, Roy Halladay, Mike Mussina, Jack Morris, Curt Schilling, Andy Pettitte, Mark Buehrle, CC Sabathia, Roger Clemens,

David Wells, Mark Mulder, Barry Zito, Billy Koch, Keith Foulke, Carl Mays, Charlie Buffinton, Bob Caruthers, Jack Stivetts, Ray Chapman

Interesting perspective and nice to see in this largely either-or era when so many people basically ignore wins. Anyone who has played and/or watched baseball for a long time knows certain pitchers posses intangible qualities that allow them to garner unlikely wins. They're the guys who can get burned by a couple of bad calls and a three-base error and a passed ball or some combo to that effect. They could be facing an ace who is cruising, but they won't blame teammates or make excuses. They bear down and keep their team in it, because as Joaquin Andujar said, "You can sum up the game of baseball in one word: 'You never know.'"

ReplyDeleteHudson compares to Schilling, who is a clear HOFer, more favorably than I had previously thought. It's a shame that some people refuse to recognize the greatness of Schilling's career. But that condition isn't unique to baseball in the US. It is possible to endorse a career or a book or whatever without liking a person or advocating certain views. I wonder if people in this society, which has been deeply divided in many ways for a long time, will ever accept that truth.

Unfortunately, when we refuse to recognize greatness (or admit mistakes, etc.) we lose objectivity, Truth loses meaning and integrity becomes an illusion.

Thank you for taking the time to read the article, Jeff. I enjoyed reading your comments. You make some great points here. Anytime you can work a Joaquin Andujar quote into a comment, you get a thumbs up from me

Delete