Over the years I have come across many articles about who is the best player at each position not in the Hall of Fame. Usually those articles only include a sentence or two about the players chosen. I decided to take a more in depth look at the players I chose, what may have kept them from being elected to the Hall of Fame, and their chances in the future. In

part one, I looked at the infield, catcher, and starting pitcher. Part two centers on the outfield, designated hitter, and relief pitcher. As I stated in part one, you won't see any accused or proven PED users at any of these positions since many of the players I have chosen to include have had their careers overshadowed by PED users' tarnished achievements.

Left Field: Tim Raines ('79-'02) 2502G 2605H 1571R 170HR 980RBI .294BA .385OBP 123OPS+ Highest HOF vote 37.5%-2011 Yrs on ballot-4

|

| Tim Raines 1986 Topps |

Tim Raines was the NL's premier leadoff hitter and base stealer of the 1980's but he had the misfortune of having his career coincide with that of

Rickey Henderson, arguably the greatest leadoff hitter and base stealer of all-time. Both Raines and Henderson were decent outfielders who each boasted a higher batting average, on base percentage, and better than average power for a leadoff hitter. "Rock" led the league in stolen bases four years in a row, from 1981 to 1984, and finished in the top-five several other years. However, Henderson led the league in stolen bases twelve times, over a 19-year span. Raines stole 808 bases in his career, good for fifth all-time, with an 84.7% success rate compared to Henderson's 80.8%. Yet, Henderson was, by far, the most prolific base stealer in baseball history, swiping an all-time high 1,406 bags.

While it is true Raines generally falls short in comparison to his contemporary Henderson, "Rock" stands tall when measured against other prominent base-stealing leadoff hitters. Raines finished his career with an impressive .385 OBP and, along with Henderson, often stayed on par with the league leaders in that category--which almost seems like it should be expected of a base stealing leadoff hitter--yet Raines and Henderson are the exception rather than the rule. By contrast, Willie Wilson and Vince Coleman, two other notable base stealing leadoff hitters of the 80's, finished their careers with OBPs of .326 and .324, respectively. In earlier generations, All-Star leadoff hitters Maury Wills (career .330 OBP), Bert Campaneris (career .311 OBP), and Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio (career .311 OBP) each dominated the stolen bases leaderboards but struggled to make it on base a third of the time. In fact, none of these famous leadoff hitter's best OBP season even equaled Raines' career .385 mark, with Luis Aparicio coming the closest with a .372 OBP in 1970.

Raines' career numbers stack up favorably to another Hall of Fame leadoff hitter,

Lou Brock. Raines and Brock have similar career batting averages of .294 and .293, respectively, as well as comparable slugging percentages of .425 and .410, however, Raines' .385 career OBP greatly exceeds Brock's .343 career mark. While it is true that Brock did play the bulk of his career during a pitcher's era, only in Brock's best OBP season, .385 in 1971, did the Cardinals speedster even match Raines' career OBP. Moreover, Raines' 123 adjusted OPS+ and 64.6 WAR outshine Brock's respective career totals of 109 and 39.1. Raines and Brock both spent most of their careers as left fielders and while neither player was considered Gold Glove caliber, Raines' .987 career fielding percentage far exceeds Brock's .959 mark.

|

| Tim Raines 1991 Topps |

Brock, however, was at his best in the postseason, batting .391 in three World Series and playing a big part in two Cardinals championships. Raines, on the other hand, batted a respectable .270 in the postseason and also won two World Series rings, albeit as a part-time player for the late 90's Yankee dynasty. In addition, Brock set both the single season and all-time career records for stolen bases (each of which were later broken by Rickey Henderson) and also surpassed 3,000 career hits. Yet, Raines' ability to draw walks gave the former Expo a 3,977 to 3,833 edge in career times on base despite having 876 less career plate appearances. Raines may not have set the stolen base records that Brock did but was the much more successful base stealer, swiping 808 bags at an 84.7% success rate while Brock was more prolific, nabbing 938 bases--though he was only successful 75.3% of the time. Furthermore, while Brock did lead the league in stolen bases eight times, compared to Raines' four, he also led the league in being caught stealing seven times, a dubious honor Raines never held. Raines was also better at making contact, never striking out more than 83 times in a season, while Brock fanned 100-plus times in nine different seasons and finished his career with 1,730 strikeouts--trailing only Willie Stargell for the most ever at the time of his retirement in 1979. Despite this, when Brock became eligible for the Hall of Fame, the former Cardinal was voted in on his first try with 79.7% of the vote. That is not to say Brock's career wasn't Hall of Fame worthy, although, by contrast, Raines--who lacked Brock's records and milestones but also lacked many of Brock's weaknesses--didn't even come close to election on his first try, drawing only 24.3% of the vote.

One blemish on Raines' career that may be costing the speedster some votes is his early career cocaine use. During the middle of the 1982 season, when Raines realized his drug use had became a

problem, he met with the Expos front office and agreed to start seeing a psychiatrist to combat his addiction. Additionally, at season's end Raines voluntarily checked into rehab. In the ensuing public fall-out caused by Raines' cocaine use, the speedster was regretful, honest, and up front about his drug use. Fortunately, Raines was able to get clean and was not involved in any drug or other scandal for the balance of his career. Some Hall of Fame voters have categorized cocaine use, like steroids, as a performance enhancer. However, Raines suffered a noticeable drop off in performance during the 1982 season, which the speedster attributed to his drug use, and in fact, had his finest seasons in the years immediately after he got clean. Furthermore, admitting early career cocaine use didn't stop Paul Molitor from being elected to the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility in 2004. What is rarely brought up is Raines' battle with lupus that brought a premature end to his 1999 season and threatened to end his career all together. "Rock"

courageously battled back and was able to return to the majors for the 2001 and 2002 seasons, during which he sported an impressive .381 OBP and even played a few games alongside his son, Tim Jr. In addition, Raines also lost playing time during both the 1981 and 1994-95 baseball strikes.

Out of all the players chosen for each position in this two part article, Raines has the best chance of one day being elected to the Hall of Fame. After a weak 24.3% debut on the ballot, "Rock" surprisingly fell to 22.6% the following year--the same year base-stealing contemporary Henderson was elected on his first try with 94.8% of the vote. Fortunately for Raines, the next two ballots saw promising increases to 30.4% and 37.5%--exactly halfway to the 75% needed for election. If Raines is able to continue his current upward trend, he should be elected with a few years to spare. However, with a glut of surefire Hall of Famers (

Greg Maddux, Randy Johnson, Ken Griffey Jr., etc.), controversial candidates tarnished by PED use allegations (

Barry Bonds,

Roger Clemens, Gary Sheffield, etc.), and a poor man's version of himself (Kenny Lofton) set to crowd the ballot in the next five years, a continued upward trend toward election is not a given.

Center Field: Dale Murphy ('76-'93) 2180G 2111H 1197R 398HR 1266RBI .265BA .346OBP 121OPS+ Highest HOF vote 23.2%-2000 Yrs on ballot-13

|

| MVP Dale Murphy 1984 Donruss |

I'm sure someone has probably said it before: What a player does in his twenties sets him up for a Hall of Fame career--but it is actually what he does in his thirties that makes or breaks his Hall of Fame chances. Perhaps no player is a better example of this than

Dale Murphy. In his twenties, Murphy seemingly could do it all, he led the league in such categories as home runs, RBI, slugging percentage, walks, and runs scored. At their peak, few players have been as dominant and as well rounded as Murphy, who in 1983 became only the sixth man in baseball history to hit more than 30 home runs and steal 30 bases. In addition, Murphy won back-to-back MVP awards in 1982 and 1983, five straight Gold Gloves in center field, played in 740 consecutive games, and even led the (at the time) long suffering Atlanta Braves to the postseason in 1982. By age thirty, the former Braves slugger had already hit 237 home runs with a slash line of .278BA .357OBP .850OPS and an adjusted OPS+ of 130. After turning thirty, Murphy had a decent year in 1986 and one more excellent one in 1987 before the bottom seemed to drop out on the slugger's career. From 1988 until the end of his career, Murphy was a shell of his former self, only managing a line of .234BA .307OBP .702OPS and a below league average adjusted OPS+ of 96.

Murphy's final career numbers of just over 2,000 hits and just under 400 home runs put him in the company of both Hall of Famers and non-Hall of Famers. One such Hall of Famer, Jim Rice, had a dominant peak similar to Murphy's and also quickly faded in his early thirties. When Murphy first appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot in 1999, only Dave Kingman and Darrell Evans had hit more home runs and not been elected to the Hall of Fame. However, with the Steroid Era and its tainted records in full swing, Murphy's numbers were already beginning to look paltry by comparison. In his first year of eligibility, Murphy collected 19.3% of the vote, not a bad total when you consider future Hall of Famers

Nolan Ryan, George Brett, Robin Yount, and Carlton Fisk all debuted on the ballot that year. Murphy made a modest increase the next year to 23.2% before dropping over the next several years all the way down to 8.5% by 2004. Since then his support has been up and down, always right around 10%, with Murphy tallying 12.6% on the latest ballot.

|

| Declining Dale Murphy 1992 Topps |

In his prime, Murphy was a rare breed whose five-tool skills arguably made him the best player in the game. Yet, the Braves slugger was known as much for his good deeds off the field as he was for his accomplishments on it. In 1987, Murphy was named

co-Sportsman of the Year by Sports Illustrated, largely due to his charity work. If there was ever such a thing as a "Hall of Fame Human Being," by all accounts, Dale Murphy would be it. Although, with stagnated support and just two years left on the ballot, it looks as if Murphy's only chance for the Hall of Fame will be through the Veterans Committee.

Right Field: Dwight Evans ('72-'91) 2606G 2446H 1470R 385HR 1384RBI .272BA .370OBP 127OPS+ Highest HOF vote 10.4%-1998 Yrs on ballot-3

When younger Red Sox fans think of the number 24 at Fenway, they generally think of Manny Ramirez, his up and down seven and a half year saga with the club, the joy and the stress he caused with his "Manny being Manny" attitude, the two long sought World Series wins he helped yield, and his controversial trade and embarrassing exit from the team. However, when most die-hard, long suffering, pre-Red Sox Nation fans think of the number 24 at Fenway, they remember

Dwight Evans, his outstanding glove-work near Pesky's Pole in right field, his mid-career emergence as a power-hitter, his unquestioned work ethic, and his dedication to the team. For nearly two decades, "Dewey" was a dependable, steady presence during Boston's ups and downs. He played important roles on the 1975 and 1986 pennant winning clubs that came up just short to the Reds and Mets in two classic World Series, battled head-to-head against both the "Bronx Zoo" Yankees of the late 70's as well as the Mattingly/Winfield led Yankees of the 80's, and was still a major contributor at the end of his Sox career when Boston was swept out of the ALCS by the Athletics and their mighty "Bash Brothers" in 1988 and 1990.

|

| Dwight Evans 1975 Topps |

For the first half of his career, Evans was more known for sure-handed glove and strong throwing arm in right field than his bat. In fact, "Dewey" won his first of eight Gold Gloves in 1976 after highlighting his defensive prowess with a tie preserving catch and assist in Game 6 of the previous year's World Series that helped set the stage for Carlton Fisk's memorable game-winning home run. During the 1980 season, Evans worked with hitting coach Walt Hriniak, who changed his batting stance, and was able to

evolve into one of baseball's best hitters, tying for the league lead in home runs the following year. Moreover, during the decade of the 1980's, Evans led the AL with 256 home runs and all of baseball with 605 extra base hits. After 19 years with Boston, "Dewey" ended his career after playing one season with the Baltimore Orioles. Although he was past his prime, Evans still managed to get on base at a more than respectable .393 clip in his final season.

Evans finished his career with nearly 2,500 career hits, almost 400 home runs, and a second half career surge along with a trio of recent playoff appearances fresh in voter's minds. Yet when the BBWAA votes were counted, Evans only managed 5.9% of the vote on a weak Hall of Fame ballot in which four-time holdover Phil Niekro was finally elected and the only other first-time candidate to draw decent support was former Pirates slugger Dave Parker with 17.5%. On his second ballot, Evans made a moderate increase to 10.4%, only to drop off the BBWAA ballot for good, one year later, when his support tumbled to 3.6% on a crowded ballot that included first-time nominees Nolan Ryan, George Brett, Robin Yount, and Carlton Fisk.

For the greater part of his career, Evans was overshadowed by fellow outfielder and future Hall of Famer

Jim Rice. During the first half of his career, Evans was generally batted near the bottom of the order, while Rice was batted in the heart of the order, due in large part to Rice's higher batting average. In fact, more than three quarters of Rice's career plate appearances came at third or fourth in the batting order compared to less than 15% of Evans' plate appearances coming at those spots. Even during his peak years in the 1980's, "Dewey" was usually batted second or sixth while Boston managers continually used declining superstars such as Rice and Carl Yastrzemski or overrated hitters like Tony Armas and Bill Buckner in the three and four holes. Underrated by even his own club, Evans was still able to put up strong RBI and runs scored totals despite being moved all around the batting order. In fact, over the course of his career, Evans had 434 or more plate appearances at each of the nine spots in the order.

|

| Dwight Evans 1986 Topps |

In the decade plus since Evans fell off the Hall of Fame ballot, writers and fans alike have begun to look for a deeper understanding of baseball statistics. Books like "Moneyball" and writers such as Bill James have brought overlooked stats such as OBP and OPS+ to the forefront and sabermetric stats like WAR are now viewed alongside the more traditional, easily quantified stats such as batting average, home runs, and RBI. "Dewey's" strong performance in these overlooked and sabermetric statsitics underline how great a player he was. In fact, Evans edges former teammate Rice in career OBP (.370 to .352), is on par with him in career OPS+ (127 to 128), and greatly outpaces the Hall of Famer in career WAR (61.8 to 41.5).

"Dewey's" lack of Hall of Fame support most likely stemmed from his .272 lifetime batting average, a relatively low total for a Hall of Famer. When Evans fell off the Hall of Fame ballot after the 1999 election, on base percentage had yet to emerge from the shadow of batting average. However, over the next several years, the "Idiot" Red Sox and "Moneyball" Oakland Athletics teams, along with their young general managers, Theo Epstein and Billy Beane proved that building teams on undervalued statistics such as OBP rather than just traditional stats like batting average was an excellent strategy. Had Evans debuted on the ballot during this time, it is likely his excellent .370 career OBP would have gained him more than enough votes to stay on the ballot and in the following years a focus on his strong 61.8 career WAR may have gathered the underrated slugger enough support to eventually be elected. Both undervalued stats like OBP and sabermetric stats such as WAR along with batting average and other traditional stats will play a part in the debate when "Dewey's" Hall of Fame case is re-opened the next time the Expansion Era division of the Veterans Committee convenes in 2013.

Designated Hitter: Edgar Martinez ('87-'04) 2055G 2247H 1219R 309HR 1261RBI .312BA .418OBP 147OPS+ Highest HOF vote 36.2%-10 Yrs on ballot-2

When 41-year old

Edgar Martinez finally decided to call it a career at the end of the 2004 season, the slugger had accomplished a rare feat in this day and age: he had played his entire career with one team, the Seattle Mariners. Martinez's 18-year odyssey with the Mariners predated Ken Griffey Jr.'s arrival in Seattle and spanned to include the club's metamorphoses from league doormat to perennial contender, all four of the franchise's playoff appearances, and a move from the dreary Kingdome to beautiful Safeco Field, before finally seeing its conclusion a few seasons into the "Ichiro Era."

Few players have meant more to a franchise than Martinez did to the Mariners during the 1995 season. Despite losing superstar Ken Griffey Jr. to injury for almost half the season, the Mariners were able to catch and pass the California Angels for their first division title. This was, in large part, behind the strength of Martinez's bat which led the AL with an eye popping 52 doubles, .356 batting average, .479 OBP, and 185 adjusted OPS+. During Game 4 of the ALDS, with the team facing elimination against the New York Yankees, Martinez erased most of a five run deficit with a 3-run home run off Scott Kamieniecki in the bottom of the 3rd and, later, in the bottom of the 8th it was Martinez's grand slam off closer John Wetteland that broke a 6-6 tie to force Game 5. The following night, Martinez finished off the Yankees with a memorable 11th inning two-run walk off double against Yankees hurler Jack McDowell to bring the franchise its first playoff series win after nearly two decades of futility. Martinez, his teammates, and their accomplishments during the 1995 season went a long way toward getting the team the new ballpark at Safeco Field that would keep the franchise in Seattle.

|

| 3B Edgar Martinez 1992 Bowman |

Martinez's excellent 1995 season was also his first as the team's designated hitter after the team moved him from 3rd base. Prior to the move to DH, Martinez had put up three impressive offensive seasons, including an All-Star 1992 season in which he led the AL with a .343 batting average, before spending a large portion of the 1993 season and some of the 1994 season on the disabled list. Much like Paul Molitor, a permanent move to DH helped keep Martinez off the DL and in the line up. In fact, for the next nine years Martinez averaged nearly 40 doubles, over 25 home runs, 100 plus RBI, along with a .321 batting average, .438 OBP, and a 159 adjusted OPS+.

Martinez's career .312 average, .418 OBP, and 147 adjusted OPS+ have Hall of Fame immortality written all over them. However, the Mariners slugger wasn't able to stick in the big leagues as a full-time player until he was 27, so his 2247 career hits are a touch below Cooperstown norms. In addition, over 70% of his plate appearances came as a DH and depending on the Hall of Fame voter that may cost Martinez some votes. Harold Baines, for example, was announced as the DH for more than half his plate appearances and fell off the Hall of Fame ballot after just a few elections despite 2,866 career hits. However, Martinez was a much more dominant hitter than Baines, whose impressive career totals were more a product of longevity rather than dominance. First ballot Hall of Famer Paul Molitor batted as a DH for almost half his career, yet easily made his way to Cooperstown, due in large part to his 3,319 career hits. Another debate that is brought up in Martinez's Hall of Fame candidacy is whether not playing in the field should be as great a penalty as below average fielding. Willie McCovey and Willie Stargell were never bestowed with Gold Gloves during their playing careers and are both several defensive wins below replacement for their careers. The late Harmon Killebrew's glove was hidden at both corners of the infield and also out in left field before he finally finished his career as a DH. However, suspect fielding didn't keep any of these men, all dominant hitters, out of Cooperstown.

|

| DH Edgar Martinez 2001 UD Ovation |

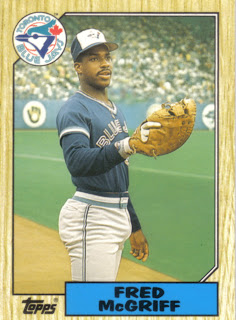

In his debut on the Hall of Fame ballot, Martinez was able to draw decent support with 36.2% of the vote. However, the former Mariner slugger saw a surprising drop to 32.9% on the latest ballot and while suffering a drop in vote totals in the second year does not necessarily doom a Hall of Fame bid--as we've seen in the recent cases of

Bert Blyleven, Gary Carter, and Phil Niekro--it certainly is not a promising trend. In the coming years, Martinez along with

Fred McGriff, another Hall of Fame candidate who debuted on the ballot in 2010 and saw decreased support on his second ballot, will find himself fighting for votes on a crowded ballot with both tarnished and untarnished stars of the Steroid Era. One thing that may help or may hurt Martinez, there's no player quite like him on the ballot.

Relief Pitcher: Lee Smith ('80-'97) 71-92 .436W% 3.03ERA 1022G 478SV 1289.1IP 1251K 132ERA+ Highest HOF vote 47.3%-2010 Yrs on ballot-9

|

| Intimidating Fireman Lee Smith 1986 Topps |

Lee Smith's career as a reliever started in the early 80's back when a bullpen's best pitcher was referred to as a fireman and entering a game in the 7th inning with the tying run on base wasn't out of the question. By the time Smith's career ended in the late 90's, firemen were a thing of the past, the top man in the bullpen was now known as the closer, and entering a game in the 9th with no runners on base had become the norm. Smith is one of the few relief pitchers to find success as both a fireman and a closer. In fact, Smith led the league in saves in 1983 during the dying days of the fireman and also led the league in saves in 1991, 1992, and 1994 as the closer in a specialized bullpen. In addition to leading the league in saves four times, Smith was a four-time runner up to the league leader in 1984, 1985, 1987, and 1995. Smith never won a Cy Young but finished as high as second, in 1991, when he set the (at the time) NL single season saves record with 47. Smith also picked up two NL Rolaids Relief awards, in 1991 and 1992, as well as one AL Rolaids Relief award in 1994. During the 1993 season, the intimidating 6'5" Smith passed Jeff Reardon as the all-time saves leader, an honor he held until Trevor Hoffman notched save number 479 in late 2006.

Thus far, only five relief pitchers have been elected to the Hall of Fame: Hoyt Wilhelm, Rollie Fingers, Bruce Sutter, and Rich Gossage, each of whom were firemen, and

Dennis Eckersley who was a closer. Over Smith's career, the intimidating reliever successfully converted 82% of his save opportunities. In fact, Smith's save success rate is higher than Wilhelm's (79%), Fingers' (76%), Sutter's (75%), and Gossage's (73%) but just below Eckersley's (85%). Although, one could make the argument that Smith's save success rate is only as high as it is because most of his saves came as a closer rather than a fireman. However, during Smith's eight seasons in Chicago, he was generally used as a fireman and successfully converted 80% of his saves.

On Smith's first appearance on the Hall of Fame ballot, in 2003, the intimidating reliever drew a promising 42.3% of the vote. At the time, Smith's vote percentage put him just behind former teammate Ryne Sandberg's 49.2% and just ahead of fireman Rich Gossage's 42.1%. However, the following year, Smith's support unexpectedly plummeted to 36.6%, the same year former closer Dennis Eckersley breezed into the Hall of Fame on his first try with 83.2% of the vote. Two years later, on a weak 2006 ballot, fireman Bruce Sutter was finally elected on his thirteenth try, while Smith rebounded to 45%. However, the next year Smith's support dropped again, this time to 39.8%, just a few months after Trevor Hoffman broke his all-time saves record. In 2008, Gossage--whose increased vote totals since 2003 contrasted Smith's stagnant support--was elected on his ninth try while Smith tallied 43.3%. On the latest Hall of Fame ballot, Smith's vote percentage fell once again, this time from a personal high of 47.3% in 2010 down two percent to 45.3. On the same ballot, closer John Franco, who sits one spot below Smith with 424 career saves, fell off the BBWAA ballot for good after gaining only 4.6% of the vote on his first try.

|

| Intimidating Closer Lee Smith 1991 Topps |

Since his 2003 debut on the Hall of Fame ballot, Smith's vote percentage has fluctuated between 36.6 and 47.3%. It would appear that one-third of the voters strongly back the intimidating reliever's candidacy regardless of the strength of the ballot. One reason why Smith may have struggled to sway more voters is his .436 career win percentage. Win/loss record is not considered the best way to evaluate a reliever but Smith's win percentage is lower than each of the five relievers in the Hall of Fame. What's more, with a series of crowded Hall of Fame ballots on the horizon and closers Trevor Hoffman and Billy Wagner likely to join the ballot in 2016, it is doubtful Smith's see-saw support will rise to 75% and the intimidating reliever will probably need to wait for the Veterans Committee to weigh the sum of his career, fireman and closer.

--Related articles: